How Russia keeps raising an army to replace its dead

For Russian men, war now advertises itself like any other job.

Offers for front-line contracts appear on the messaging app Telegram alongside group chats and news alerts, promising signing bonuses of up to $540,000 — life-changing money in a country where average monthly wages remain below $1,000. The incentives go beyond cash, with pledges of debt relief and free child care for soldiers’ families and guaranteed university places for their children. Criminal records, illness and even HIV are no longer automatic disqualifiers. For many men with little to lose, the front has become an employer of last resort.

Behind the flood of offers is a coordinated recruitment system run through Russia’s more than 80 regional governments. Pressured by the Kremlin to deliver manpower, the regions have become de facto hiring hubs, competing with one another for contract soldiers. What began as a wartime fix has hardened into a quasi-commercial headhunting industry powered by federal bonuses and local budgets. Regional authorities contract HR agencies, which in turn deploy freelance recruiters to advertise online, screen applicants and shepherd men through enlistment paperwork.

Any Russian citizen can now work as a wartime recruiter, with many operating as freelance headhunters who earn commissions for delivering bodies to the front. Axel Springer Global Reporters Network, which includes POLITICO, reviewed recruitment channels across Russia and interviewed multiple recruits and recruiters for this report.

This labor defense market is being closely studied in Western capitals, where the continued growth of Russia’s army — despite having around 1 million soldiers killed or severely wounded since 2022 — has stunned intelligence services and vexed diplomats, who see the increase as crucial to understanding the country’s posture in peace negotiations and the possibility of future expansion into neighboring territory.

“Assuming that Putin is able to continue to fund the enormous enlistment bonuses (and death payments, too) and to find the manpower currently enticed to serve,” former CIA Director David Petraeus told POLITICO, Russia “can sustain the kind of costly, grinding campaign that has characterized the fighting in Ukraine since the last major achievements on either side in the second year of the war.”

Russia’s ability to sustain manpower levels amid massive battlefield losses helps explain why, four years into the invasion, President Vladimir Putin appears more convinced than ever that he can force Ukraine to accept his terms — whether through diplomacy or a grinding war of attrition. Speaking to Russian journalists on Nov. 27, Putin made clear the war would end only if Ukrainian forces withdrew from the territories Russia claims — otherwise, he warned, Moscow would impose its terms “by armed force.”

A marketplace for soldiers

When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, Olga and her husband Alexander were running a small hiring operation in Moscow — placing construction workers, security guards and couriers in civilian jobs. About 18 months ago, they pivoted to something far more lucrative via Russia’s main classified ads platform: recruiting riflemen, drone operators and other soldiers for the war.

“Our daughter saw a job ad on Avito looking for recruiters, and that’s how it all started,” Olga told POLITICO in a series of voice messages over WhatsApp. Her profile picture displays the Russian coat of arms. (Olga and Alexander’s surname has been withheld to protect their anonymity under fear of governmental reprisal.)

As what it once expected to be a blitz has become a war of exhaustion, the Kremlin has reengineered its mobilization accordingly. In September 2022, Putin announced what he called a “partial mobilization” of 300,000 reservists, triggering a surge of public anger and emigration as hundreds of thousands fled the country to avoid being sent to fight. At the same time, the state opened its prison gates to the battlefield, luring inmates into uniform with promises of clemency and pay.

The approach worked, establishing a new blueprint: less coercion, more cash. To bring in volunteers who would not qualify for the draft because of age, health or lack of prior military service, the Kremlin targeted society’s most vulnerable — from prisoners to migrant workers and indebted men — by raising wages, offering lavish signing bonuses and selling military service as a path to dignity and survival. In September 2024, Putin formalized the strategy by ordering that the armed forces grow to 1.5 million active-duty troops. The sales pitch changed, too: subpoenas and summonses were replaced by money, benefits and appeals to manhood.

“These measures target a specific demographic: socially vulnerable men,” said political scientist Ekaterina Schulmann, who studies Russian government decision-making as a lecturer at the Osteuropa Institute in Berlin. “Men with debts, criminal records, little financial literacy — or those trapped by predatory microcredit. People on the margins, with no prospects.”

For several months, Alexander and Olga worked for a company they found through Avito before going independent and growing their business. “Now recruiters work for us — 10 people,” Olga said.

The couple do most of their headhunting on the messaging app Telegram, across a vast ecosystem of channels now devoted to wartime hiring. In one group with more than 96,000 subscribers and a profile picture labeled “WORKING,” as many as 40 recruitment ads are posted per day, advertising openings for infantrymen and drone pilots alongside detailed bonus offers from rival regions.

Each post is essentially a wage bid. While wages remain generally constant, the regions typically compete for workers by bidding up the value of labor through incentives like signing bonuses. While the Kremlin last year introduced a minimum bonus benchmark of 400,000 rubles ($5,170) via presidential decree, the amounts on offer now fluctuate wildly. Recruiters steer applicants to whichever territory is currently paying best.

“We help with documents and put them in touch with regional officials,” Olga explained. “And then we pray — that they come back alive and well.”

The couple declined to say how much they earn per recruit. But, as with bonuses offered to volunteers, recruiter pay appears to vary widely by region. Another recruiter who spoke to POLITICO confirmed figures previously published by the independent Russian outlet Verstka, which put commissions at between $1,280 and $3,800 per signed contract.

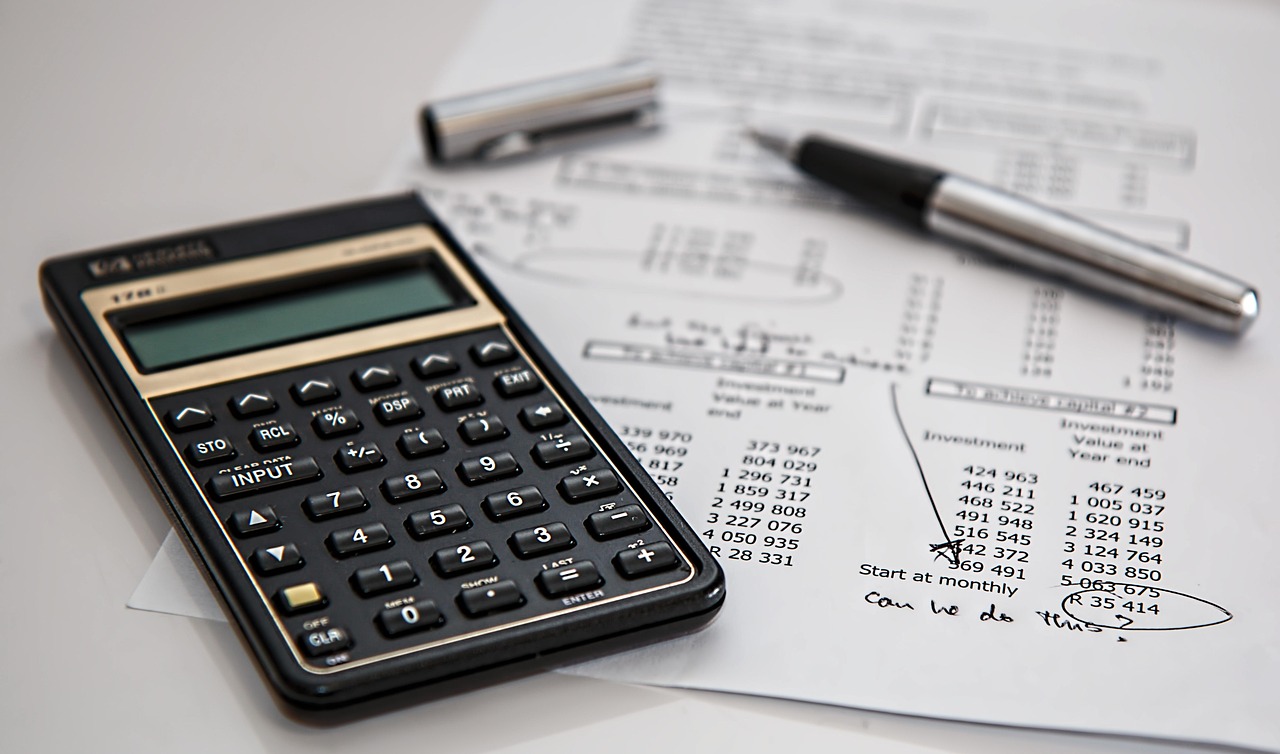

Russian regions are tapping reserve funds to maintain recruitment levels. According to a review by independent outlet iStories, just 11 regions had budgeted at least $25.5 million on recruiter payments — amounts comparable to regional spending on health care and social services.

An analysis by economist Janis Kluge of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, based on data from 37 regions, shows that average signing bonuses have now climbed to roughly $25,850, including federal payments. In early 2025, increased incentives triggered a surge of volunteers. In places like Samara, bonuses rose to more than $50,000 in summer, enough to buy a two-bedroom apartment. (In some regions, bonuses have recently fallen, which likely indicates they successfully recruited an above-average number of volunteers and had already met their quotas.)

For many families, military service has become one of the few routes to upward mobility. In many regions, weak local labor markets leave few alternatives. The more precarious the economic outlook, the stronger the recruitment pipeline.

“This kind of money can completely transform a Russian family’s life,” said Kluge. “The program works surprisingly well, but it has become far more expensive for the Kremlin.”

How the war was staffed

This recruiting machine helps to bring roughly 30,000 volunteers into the Russian armed services each month, enough to offset its heavy casualty rate and sustain long-term operations. The Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies estimated this summer that Russia had lost about 1 million killed and wounded — in line with estimates from British and Ukrainian officials.

Moscow is not relying solely on volunteers to fill its ranks. A law signed several weeks ago shifts Russia’s conscription system — which drafts medically fit men aged 18 to 30 not yet serving in the reserve — from biannual cycles to year-round processing. Experts say the change effectively creates a permanent recruitment infrastructure, enabling the Defense Ministry to funnel more people into the armed forces.

“They are moving forward, but they don’t care about the number of people they lose,” said Andriy Yermak, who as head of the Ukrainian Presidential Office served as the country’s lead peace negotiator before resigning on Nov. 28 amid a corruption investigation. “It’s important to understand that we are a democratic country, and we are fighting against an autocratic one. In Russia, a person’s life costs nothing.”

Ukrainian units, by contrast, are stretched thin; in many places, they can barely hold the line. Ukrainian officers told POLITICO that in parts of the eastern front, there are as many as seven Russian soldiers for every one of theirs. This dynamic has been exacerbated by tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers who, over the past year, have left their posts without authorization or abandoned military service altogether.

Russia’s personnel advantage is one reason its army now seizes Ukrainian land every month roughly equivalent in size to the city of Atlanta. As Kyiv relinquishes territory, it has worked to expand foreign recruitment, drawing volunteers from across the Americas and Europe.

German security officials say Putin is well-positioned to hit a declared target of a 1.5 million–troop army next year. That rapid industrial and military buildup has rattled European policymakers, who increasingly see it as preparation for military action beyond Ukraine.

“Russia is continuing to build up its army and is mobilizing on a scale that suggests a larger military confrontation with additional European states,” said German Bundestag member Roderich Kiesewetter, a security expert from Chancellor Friedrich Merz’s party.

A fighter by necessity

Anton didn’t join the military because he believed in the war. He slipped into the army after a financial collapse. By the time the 44-year-old father of three from the Moscow region walked into a military recruitment office last year, he felt he had run out of options. He was unemployed, drowning in debt and facing a possible prison sentence over a fraud case that made finding legal work nearly impossible. (Anton’s name was changed to protect his anonymity under fear of governmental reprisal.)

Opening Telegram, he also kept seeing persistent ads promising lavish bonuses. “My wife was on maternity leave, my mother is retired — the family depended on me,” Anton told POLITICO in voice messages sent over Telegram. “During one argument, my wife said: ‘It would be better if you went to war.’ A month and a half later, I signed the contract. It felt like the only way out.” In Anton’s case, no recruiter was involved — he went to the recruitment center on his own.

The contract promised Anton about $2,650 a month, plus a signing bonus from the Moscow region of roughly $2,460, more than 10 times what he had earned under the table as a warehouse worker and courier. He was dispatched to the Pokrovsk sector in Ukraine’s Donetsk region, at a remove from direct combat — though, as he puts it, under “occasional shelling” — keeping his unit’s drones operational.

There, said Anton, he met many men who, like him, had been unable to make ends meet in civilian life. “Some are paying alimony, some were sent by creditors to work off their debts,” Anton said. “There’s no patriotic talk here — no ‘for victory’ or ‘for Putin.’ Nobody speaks like that. Everyone is tired. Everyone just wants to go home.”

In July 2025, Anton received a state decoration for his service, which may help clear his criminal record. “That was another reason I signed,” he said. “It was the only way to avoid prosecution — either die or earn a medal.”

Eluding prison time remains a strong motivator for many. A relative of a missing soldier from the Moscow region described how 28-year-old Ivan, a cook, was arrested for drug trafficking in 2025. “He signed the military service declaration in custody and asked the court to replace his sentence with service,” the relative said. Within a week, he was deployed to the front. Ivan disappeared in April after less than a month in combat. His wife and 1-year-old son have heard nothing since. (Ivan’s name was changed at the family’s request, for fear of retribution.)

While tens of thousands have enlisted from Russia’s wealthiest urban centers, according to official databases and analysts, most recruits come from Russia’s economically depressed regions, where life has long been defined by poverty, crime and alcoholism.

“For many men, this is the last opportunity to build a life that feels meaningful,” said Alexander Baunov of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. “Instead of dying as failures in their families’ eyes, they die as heroes on the front.”

For the men volunteering — often treated as expendable by their commanders — the war has become a high-risk lottery for a better life. Survival brings transformative earnings. Even severe injuries come with fixed payouts: roughly $12,000 for a broken finger and $36,000 for a shattered foot.

During brief trips closer to the front to deliver equipment, Anton said he was repeatedly targeted by Ukrainian drones. On one occasion, one exploded just meters from him. Even that narrow escape wasn’t enough to make him reconsider.

“My financial situation improved significantly. It may sound sad, but for me personally, signing the contract made my life better,” Anton said. “The hardest part is being far from my children. But even knowing that, I would do it all over again.”

:quality(85):upscale()/2023/09/18/918/n/1922398/a1136b676508baddc752f5.20098216_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/10/09/670/n/1922283/00b944c868e7cf4f7b79b3.95741067_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/10/15/765/n/1922398/29c37a6e68efd84bb02f35.49541188_.jpg)

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/09/09/891/n/1922283/7222624268c08ccba1c9a3.01436482_.png)